Reducing Risk from General Market Fluctuations (Systematic Risk)

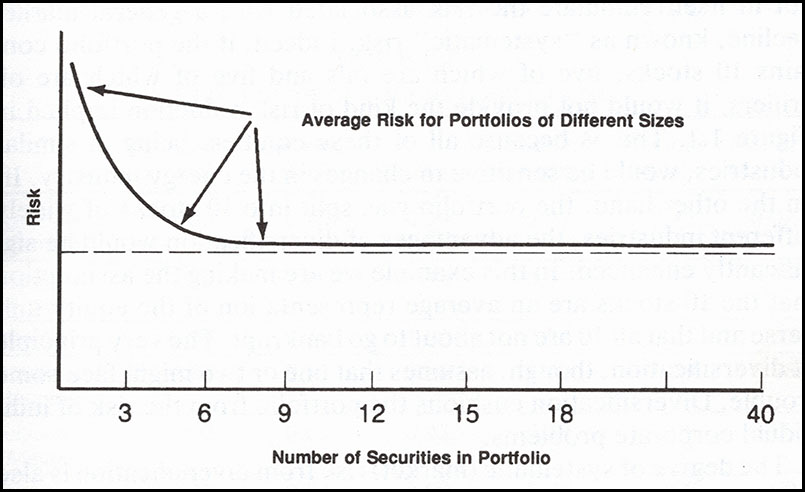

The process of diversifying into a number of different stocks does not in itself eliminate the risk associated with a general market decline, known as “systematic” risk. Indeed, if the portfolio contains 10 stocks, five of which are oils and five of which are oil drillers, it would not provide the kind of risk reduction implied in Figure 1.1. This is because all of these equities, being in similar industries, would be sensitive to changes in the energy industry. If, on the other hand, the portfolio was split into 10 stocks of widely different industries, the advantages of diversification would be significantly enhanced. In this example, we are making the assumption that the 10 stocks are an average representation of the equity universe and that all 10 are not about to go bankrupt. The very principle of diversification, though, assumes that one or two might face some trouble. Diversification cushions the portfolio from the risk of individual corporate problems.

Figure1.1 — Risk Reduction Through Diversification

The degree of systematic (market) risk from diversification is also a function of the balance of the character of the assets represented in the portfolio. This idea of similar and dissimilar movements in the relative prices of assets, or for that matter between stocks, is known as correlation. For example, a well-diversified portfolio includes a number of assets that are not closely correlated. If one performs badly, it will be offset by others that do well, i. e., that are not correlated. The two assets, therefore, have the effect of counterbalancing each other. It is always important to have some portion of your portfolio oriented toward equities and growth, but making an allocation in other asset classes, such as, cash or precious metals, which have a low correlation with equities, gives you some protection.

Balancing the portfolio with a number of instruments that are not closely related makes good investment sense. For example, stocks and gold move in different directions over relatively long periods of a year or more. In 1969, stocks lost 8.5 percent, but gold achieved a positive return of over 6 percent. Hedging you bets, i.e., spreading your risk, in these non-correlated assets makes it possible to significantly reduce your risk.

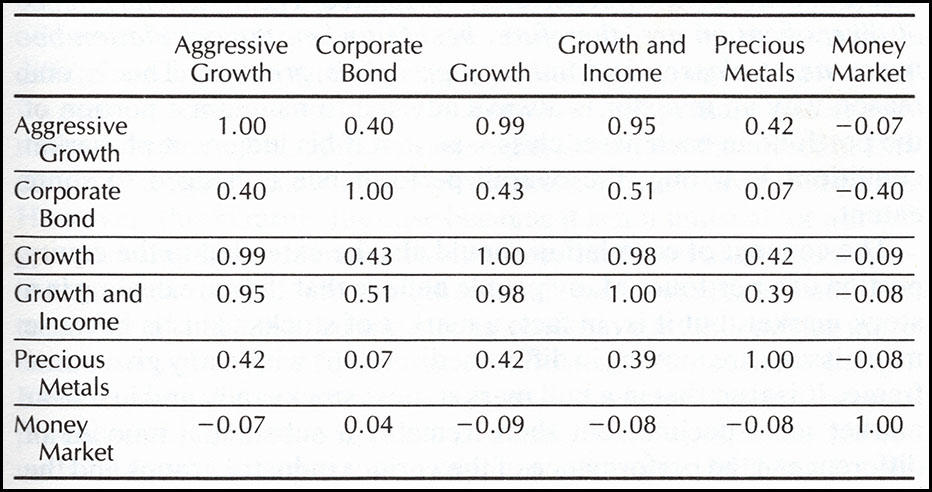

Table 1.1 shows how well or how poorly the various asset classes (bonds, stocks, and cash) have correlated historically. A reading of 1.00 indicates that the two assets are perfectly correlated, which means that combining them offers only limited benefits. For example, let’s suppose you are a conservative investor and require substantial income. This means that you would naturally gravitate to a policy of allocating a high proportion of your assets to corporate bonds. (For this exercise, we are ignoring the possibilities of asset rotation, such as, psychological ability to bear risk, etc.). In Table 1.1, corporate bonds on the vertical scale have a correlation of 1.00. In effect, diversifying into corporate bonds is not going to help because it makes no sense to diversify into an identical item.

Table 1.1 — Correlations of Various Asset Classes

On the other hand, in Table 1.1, we can see that corporate bonds correlate only about half the time with growth and income funds, so they would represent a reasonable offset. The relationship between corporate bonds and precious metal funds is even more striking since the correlation has declined to 0.07. This means that they move in the same direction less than 10 percent of the time. The same observation can be made for the relationship between corporate bonds and money market funds. Precious metals funds have the advantage in that that they are a hedge against inflation, but they produce very little in the way of income. On the other hand, money market funds do produce income, but are useless as a long-term inflation hedge.

A diversified portfolio does not necessarily imply lower returns, but inevitably guarantees a reduction in risk, provided that the assets in question are not perfectly correlated. The beneficial effects of diversification are, therefore, best felt when the correlation between asset classes and industry groups is greatest. This is one reason why an investor is always advised to maintain a portion of the portfolio in each asset class-so that if his judgment of market conditions is wrong, the overall performance is hedged to some extent.

The concept of correlation should also be extended to the equity portion of a portfolio. Many people believe that they are dealing in a stock market, but it is, in fact, a market of stocks. This is because many issues are moving in different directions within any given time frame. It is true that in a bull market most stocks rally and in a bear market most decline, but there remains a substantial amount of difference in the performance of the

various industry groups and the stocks that they represent. Even within the stock portfolio itself, it is important to diversify among industry groups that have a low correlation with one another. For example, an industry group rotation develops over the course of the business cycle. At the beginning, when the economy is digging itself out of recession, utilities

and other industries whose profits are particularly enhanced by falling interest rates put in their best price performance, and inflation sensitive stocks, such as, mines and oils, put in their worst. As the economy moves into the terminal recovery phase, when inflationary pressures are greatest, utility issues start to decline, but the market averages are buoyed by mining and energy issues, which thrive in this kind of environment. A portfolio that is balanced between a number of diverse groups is better positioned to avoid both market and non-market risk for virtually the whole cycle.

Diversification Can Also Lead to Bigger Gains

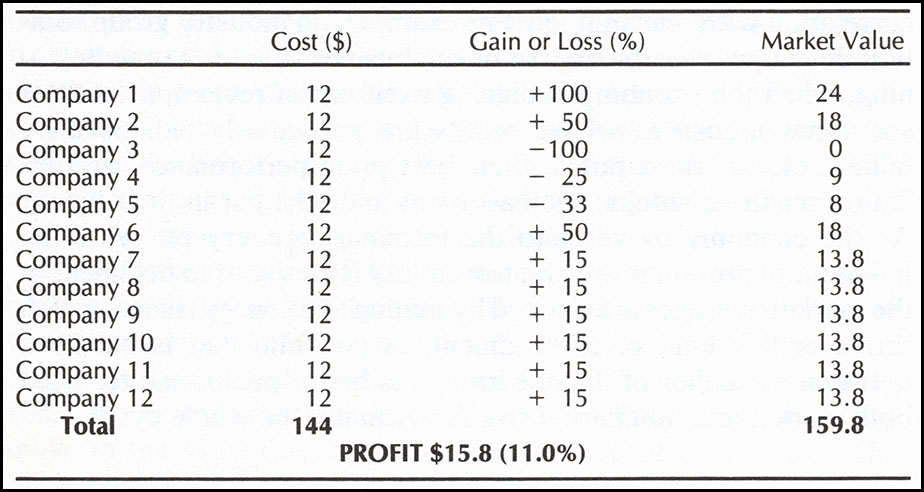

We can also look at diversification not so much from risk control, but from the more positive aspect of spreading the net in order to increase the chances of landing a big fish. Say, for example, we had decided to invest in some fast-growing junior companies. One possibility would be to limit the purchase to one or two well-researched candidates. We may find that we now own a future Xerox, but the odds would be pretty slim. On the other hand, an investment in 10 different companies would probably result in one or two very good winners, a couple of mediocre performers and, perhaps, one or two major losers. At first glance, you might think that the effect of this combination of winners and losers is more or less a zero-sum game. However, this is rarely the case because it is not unusual for a small growth company to increase two or three times in value over a two to three-year period. On the other hand, losing stocks are unlikely to go out of business, so the strong ones have a tendency to more than outweigh a 40 or 50 percent decline in another of the holdings. Even if we take an extreme case of a bankrupt stock that was purchased for $12, zero is as low as it can possibly get, while it is not unusual for a winning stock to triple or quadruple. In Table 1.2, we can see that even with one of the stocks falling to zero and two others experiencing sizable losses, the portfolio still puts in a reasonable performance with an 11 percent gain.

Table 1.2 — Diversified Portfolio of Aggressive Stocks

A classic example illustrating the folly of not adopting the principle of diversification was given by that great investment legend Roger Babson in his book Actions and Reactions. In the book, Babson recounts how a friend asked him in 1907 to recommend a stock to buy. At the time, Babson was writing a chapter on diversification and had been following 10

stocks, so he recommended all 10 to his friend. The prospect of following all 10 issues was too daunting, so Babson’s friend asked him to single out one issue. Babson recalls that during the next two years the average price of the 10 issues gained 50 percent, but the one stock he had singled out did not advance at all. Need we say more!

Excerpted from “The All-Season Investor”

Related Article: Diversification: The Medicine for Sleepless Nights, Part 1